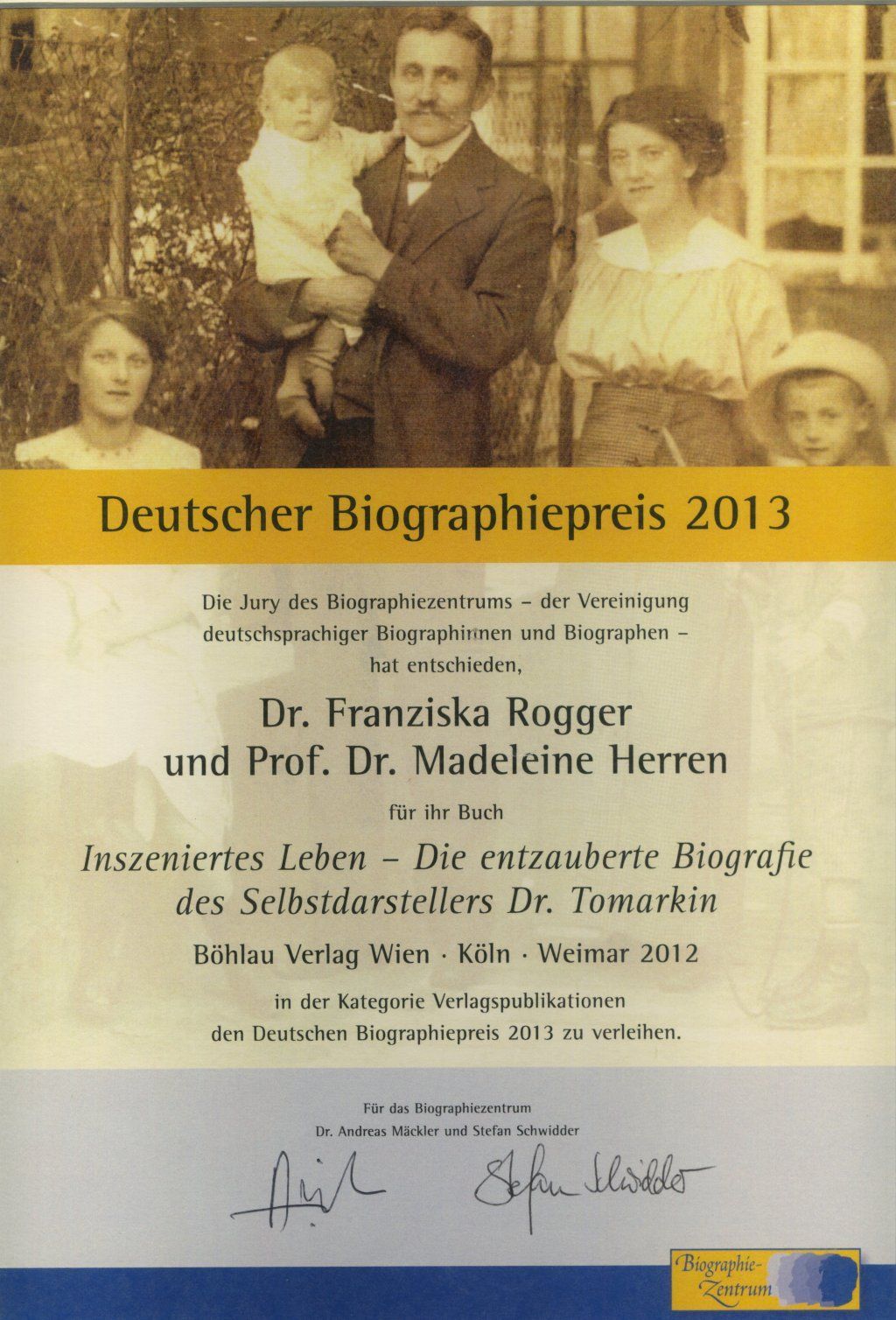

German Biography Prize 2013

for Franziska Rogger and Madeleine Herren Staged Life. The disenchanted biography of the self-promoter Dr. TomarkinBöhlau Verlag Vienna Cologne Weimar and NZZ Libro Zurich, 2012.

On the awarding of the 2013 Biography Prize: «The jury, led by biographer Dr. Andreas Mäckler, was impressed by how multifaceted and impressively the two authors demonstrated that biographies may follow life stories in a documentary way, but always remain an individual literary work that – as happened in this case – ideally becomes art.» http://www.biographiezentrum.de

Review Spiegel Online, 1.11.2013, on «Inszeniertes Leben» Impostor Leander Tomarkin Doctor Brazen His medicines were supposed to cure the worst diseases, his specialist conferences were the events of the year: In the 1930s, the alleged doctor Leander Tomarkin impressed patients and renowned colleagues with a perfectly constructed web of lies - even Nobel Prize winner Einstein fell for him. By Marc von Lüpke

«A star was born» In January 1922, the world looked to Rome with concern. Pope Benedict XV was dying. The head of the Catholic Church was suffering from severe pneumonia; the doctors in the Vatican seemed powerless. In addition, the experienced doctors had to fend off an intrusive young man who thought he had found a cure: the «Antimicrobum» was supposed to save the ailing church leader. The developer of the medicine was called Leander Tomarkin and he tirelessly persuaded the Vatican court to let him see Benedict XV. Up to this point, the supposed doctor Tomarkin, only 27 years old, had not been granted access. Now Tomarkin summoned doctors, clergy, officials and guards and wanted to convince them of his cure. He offered himself as a guinea pig to prove to the sceptics that his little remedy was harmless. Before the Pope could enjoy the "antimicrobum", Benedict XV died on January 22nd. According to Tomarkin, he only had to take a few water-soluble gelatin capsules containing a gray powder. The Pope's death was Leander Tomarkin's hour. The reporters who had been waiting for the news of the Church leader's death pounced on Tomarkin, who was now notorious in Vatican circles. He was happy to describe his fight for access to the Pope and the genius of his "antimicrobum", which supposedly could cure pneumonia. The reporters eagerly wrote down the information and soon the papers were reporting that Tomarkin had taken "a gigantic step for the benefit of humanity". One newspaper even declared: "A star was born".

A fake doctor The future - would-be - saviour of the Pope came from the Swiss town of Zollikon. Leander William Tomarkin was born there on December 3, 1895, the son of a Jewish-Russian doctor, and spent his childhood and youth with his brother Percy and his mother, who was seriously ill with polyarthritis. His parents separated when Leander was about ten years old. As a school failure, he was the problem child of the family, and was sent to a technical college so that he could at least receive a solid education in chemistry. But he failed there too - and studying was a long way off. Evidently, Tomarkin was not always very truthful. "If he can't continue as an honest person, he should just find somewhere to stay," his father wrote resignedly in 1916. Tomarkin consistently continued down this dishonest path: he awarded himself a doctorate and began to deceive those around him on a large scale. The con man had no real goal in life. Instead, he tinkered around in his father's laboratory and hoped for a great "discovery". Tomarkin was just 20 when he became the father of a son; the following year he married his son's mother. His father had to help out financially the young couple, who often moved because of heavy rent debts. Tomarkin tried to make big, quick money by selling pig bristles and vaccines, among other things. Without resounding success.

The savior of humanity The Pope's illness came at just the right time for Tomarkin in 1922. The young man now presented himself to the public as a smart and charismatic miracle doctor. In reality, however, his financial existence was in ruins. The company he had founded earlier, the company L. Tomarkin & Co. in Ascona, which was actually supposed to manufacture and sell chemical and pharmaceutical products, had failed. The Pope's death, however, had unexpectedly brought him media attention - and another coincidence played into his hands: in 1923, the cousin of the Italian king was ill - and Tomarkin's supposed miracle cure apparently made him recover. The royal family was delighted and gave Tomarkin the title of royal personal physician. This opened more doors for him in high society - with well-paying patients. Tomarkin, always of impeccable demeanor, played his role perfectly. With the round lenses of his glasses and the perfectly fitting white coat, the impostor radiated great seriousness as he posed in his laboratory with a scientifically thoughtful look. He explained to various newspapers that he did not want to use his genius for money, but for the good of humanity. He therefore did not sell the rights to his miracle cure, which could also cure typhus, tuberculosis, meningitis and malaria, to the many interested parties, but instead looked for a charitable foundation - which he would later set up himself. Until then, he lived well from his fame and from selling the "Antimicrobum" to hopeful people. He gave the chemical composition of the miracle cure as "aminoortobenzoilsulfoisoamiloidrocupronucleinforminsodico". This was nonsense, but impressive for the uninformed. Series of tests on patients went surprisingly well, such as the one in 1923 at the prestigious Roman university hospital Ospedale Santo Spirito. "I would, of course, like the patients selected to be individuals whose pneumonia is still in the early stages," Tomarkin wrote to his brother, with whom he had carried out several failed business deals in the past. Tomarkin's wish was obvious, as these patients were much easier to cure - and were better cared for as test patients.

The Tomarkin Foundation At the end of May 1924, Tomarkin left Europe. In the USA, he hoped to make influential acquaintances with plenty of money - and three years later, with a lot of charm and persuasion, he achieved his goal: the establishment of the Tomarkin Foundation Chemistry Research. The foundation was a chemistry research institute. With the successors to the "Antimicrobum" such as "Catalysan" and "Disulphamin", which he developed there, he wanted to cure even more people. Tomarkin called the benefits of his medicines "retuning treatment": cells "should be retuned by specific and non-specific stimuli". From sick to healthy, as if tuberculosis were a mood. The Tomarkin Foundation soon spread to Europe. The sophisticated city of Locarno became its headquarters. It was here that the attention-seeking Tomarkin discovered his real talent: organizing conferences. In 1930, Tomarkin invited for the first time all those who were of any rank and name in science, including the famous German surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch. Doctors from all possible disciplines gave lectures to their colleagues on their current research, while Tomarkin's strength lay less in describing his own research results than in organizing "congress-accompanying" activities: trips into nature, to museums, concerts and opulent banquets, accompanied by the charmingly chatty Tomarkin. This mixture of the presentation of top scientific research and an inspiring "supporting program" made Tomarkin's advanced training courses popular: the luminaries of the medical profession made pilgrimages to him in Locarno. The fact that Tomarkin himself only had cultural highlights to offer rather than medical ones went largely unnoticed. At another congress in 1931, he pulled off his greatest coup. "The approval of Professor Albert Einstein, who has taken over the honorary presidency of the foundation, fills us with pride," announced Tomarkin. Higher scientific honors than those of the universally celebrated Nobel Prize winner Einstein could not be obtained. Tomarkin was at the height of his fame. But the imposter's earlier frauds were to take their revenge - and destroy Tomarkin and Einstein's good relationship. In 1932, a former landlady wrote to Einstein that Tomarkin had cheated her out of 500 francs. Couldn't the famous Albert Einstein read the riot act to the "miracle healer"? Einstein took the matter to heart, putting tireless pressure on Tomarkin for almost three months until, after fairly transparent deceptions, the latter deigned to pay. Tomarkin's reputation as a selfless benefactor was damaged. The Nobel Prize winner told the shocked Tomarkin that he "no longer wanted to be associated" with the Tomarkin Foundation. Many doctors who had attended the congresses were satisfied, however. "Excellent and promising," one said. The "International Week Against Cancer" in 1938 was nevertheless to be Tomarkin's last major event of this kind. After the outbreak of World War II, he no longer felt safe in Europe because of his Jewish origins and fled to the USA.

The inventor His plan to earn money there by holding more conferences did not work out. Scientific progress had overtaken his supposed miracle cures. The biochemist Selman Abraham Waksman had just discovered a truly effective cure: antibiotics. Tomarkin now wanted to make a living as an inventor outside of medicine - but his supposedly waterproof paint turned out to be anything but waterproof. The production of artificial diamonds also remained a fantasy. Nevertheless, there were enough people who fell for his claims. So Tomarkin continued to live on the border between truth and lies - as a gifted and at the same time unscrupulous self-promoter - until his death in 1967.

For further reading: Franziska Rogger & Madeleine Herren: «Staged life. The disenchanted biography of the self-promoter Dr. Tomarkin», Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2012, 379 pages. http://www.spiegel.de/einestages/hochstapler-leander-tomarkin-der-erfinder-des-antimicrobum-a-951291.html